How Learner Agency Impacts a Learning Ecosystem

School systems are interconnected communities of learners, and shifting to learner-centered models is a complex and humbling journey. In schools that are designed for standardization, tensions can arise very quickly when you begin to promote agency and innovation. In my experience as a teacher, principal, and school superintendent, I saw firsthand how the ripple effects of changes to teaching and learning at the classroom level catalyzed unexpected and important changes in our leadership approach and management structures.

When I was the superintendent of the Vista Unified School District, the trigger for us to begin re-examining our leadership approach was a wave of requests that our facilities department received from students in our schools.

- Can we install hydration stations that work with water bottles so that we use less plastic in the school?

- Can we paint the walls of the maker space ourselves to inspire creativity and innovation?

- Can we move our furniture outside so that we can conduct learning labs in the wooded areas next to the school?

While these requests were specific to facilities, they exposed the reality that our school management team didn’t know how to prioritize, establish limits, or continue encouraging proposals directly from the kids. It wasn’t something that we had anticipated, but in retrospect, it all made sense. Once you allow, encourage, promote, and cultivate learner agency, it begins to put pressure on all aspects of the system.

None of these ideas had been part of our existing plans and now we had to decide how to respond—we had to decide how to adapt. And it was coming from the students because of changes in our instructional model.

Shifting Practices

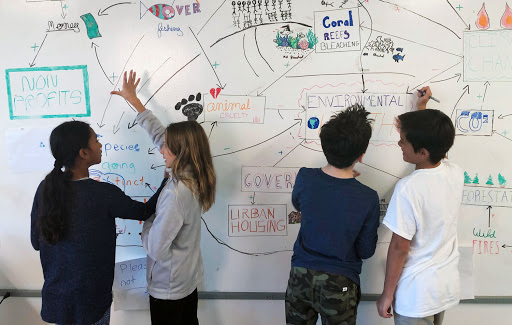

As teachers were beginning to empower a learner-centered approach, students began to engage in problems that were relevant to them. Many of these problems involved making improvements in their environment. One of the reasons that we were now receiving facility requests from the students was that they were encouraged to engage in projects aligned with their interests.

The basic flow here is that when students begin to know themselves and to create and implement their own learning pathways it requires a system-wide shift.

- At the classroom level, it requires teachers to let go of perceived control. Shifting from teacher-centered to learner-centered education means that teachers become activators of learning. For observers, it often looks like the switch from “sage on the stage” to “guide on the side,” and teachers will rightfully assert that the work is just as intense (and more rewarding).

- Site and district administrators find that when they promote this change in classroom practice, they must also adjust from a compliance and management mindset to one of empowerment and servant leadership. Many educators have reflected on how this is a difficult change that is validated by the improvements in learner engagement that they see and feel.

- In facilities and operations, someone like a Maintenance Director—who is accustomed to work tickets coming through official channels and being managed by a predictable workflow with clear boundaries—can feel like they are moving from order to chaos. In many ways, that is the tension that all educators must adapt to in support of this new model.

Leading with Outcomes

How does one ensure that there is an appropriate balance between structure and flexibility? Between coherence and individuality? Between compliance and creativity? In practice, this is an adaptive challenge and the optimal edge is dynamic and ever-changing. The answer, from my experience, is to embrace feedback to inform when and where to increase or reduce structure. This requires another shift from process to outcomes and process.

What I mean here is that the first re-orientation is to be clear on what you are trying to achieve and to use the clarity of goals as the first filter in any decision making. Those goals need to be clearly identified at every layer of the organization (district, school site, department, classroom, and student). Being tight on outcomes and loose on process creates accountability and coherence while also allowing for individuality, flexibility, and creativity in achieving those outcomes.

With clear goal alignment, the next re-orientation is to move away from following a rigid process and, instead, create and implement feedback systems on the process itself. This feedback tends to be qualitative, best achieved through conversation in context, and can be very time intensive. However, the benefits are tremendous in terms of providing a surface for meaningful input, developing relationships, and identifying creative ways to improve the process based on perspectives informed by experience.

Impact

At the end of the day, we decided to evaluate the student requests on their merits and to be as responsive and adaptive as we could be. We swapped out hydration stations and it ended up reducing waste. We allowed students to paint the walls of the maker space and found it did improve engagement. We allowed some furniture to go outside to promote outdoor learning. As a result, we met our desired outcomes and ended up improving our procedures.

It turns out that once you unleash student agency, it ripples through the community. Once you unleash student agency, many things get better that weren’t part of the original plan. In a profound way I learned that by empowering individuality we become better together.

Learn how Learner-Centered Collaborative can support your school’s shift from teacher- to student-centered learning.