A Learner-Centered Take on Homework

Is homework learner-centered? That was the question posed to our team at Learner-Centered Collaborative recently and it generated an extremely lively debate. We are guided by our vision for the future where educational ecosystems will empower all learners to know themselves, thrive in community, and actively engage in the world as their best selves. We use the term “ecosystems” intentionally as we believe that learning transcends our conventional views of classrooms and schools. We use terms like “open-walled” and “flexible learning environments” which imply that powerful learning can happen anywhere—including our homes. We also emphasize competency-based, personalized, inclusive and equitable, and authentic learning which could all occur in many different environments. The unbounded learning that is possible through this lens can develop agency, collaboration, and problem-solving skills that will be critical for individuals and communities to be successful in the present and in the future. Given this framing, homework definitely could fit within a learner-centered paradigm.

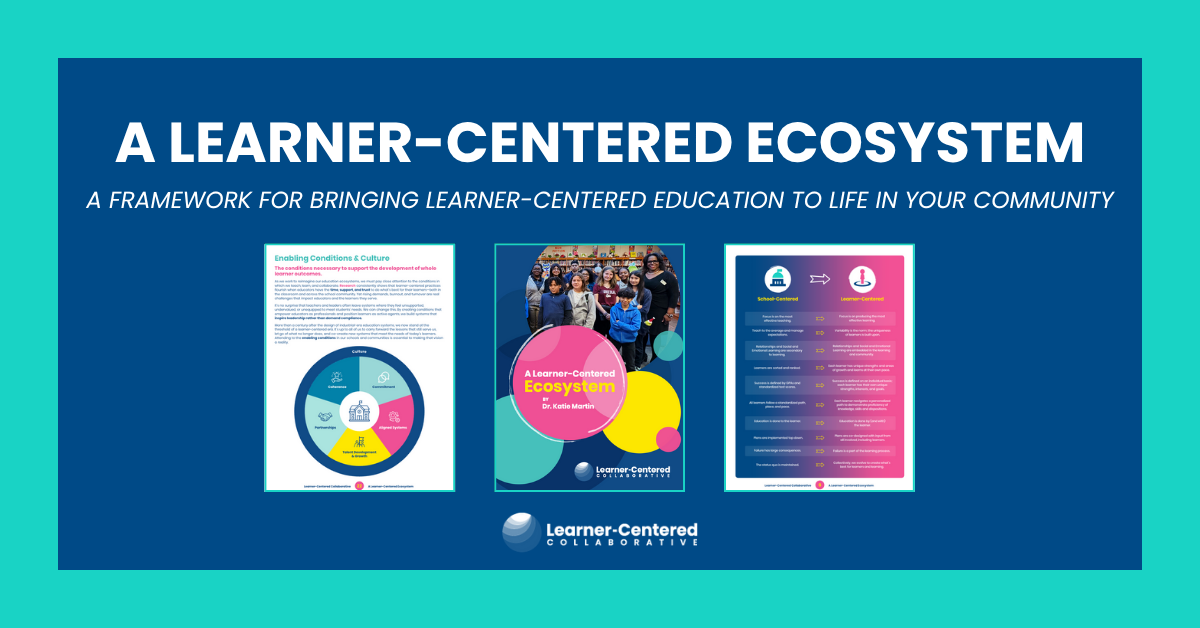

Unfortunately, it is far more common that homework is assigned through the lens of a more traditional, school-centered approach. The aims of a school-centered paradigm are fundamentally different from a learner-centered paradigm and are rooted in an era whose time has passed. As our Chief Impact Officer Katie Martin has shared, school-centered models emphasize standardization, compliance, products, and content delivery. As a result, homework is often the same for all students, focused on task completion with limited feedback, and from disconnected subject areas.

Challenges of a school-centered approach to homework

It is therefore not a surprise that students tend to develop negative views about homework, particularly when we combine the limited relevance and authenticity of the tasks with the sheer volume that we expect them to manage. Studies have shown that by the time students reach high school they are assigned more than three hours per day of homework which unsurprisingly contributes to stress, anxiety, and even burnout. A survey of over 4300 high school students found that less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor and psychologists have expressed concern about the link between homework and the development of unhealthy coping strategies such as substance use.

Families also report that homework is frustrating and stressful: “Parents are struggling to help. Four out of five parents reported that they have had difficulty understanding their children’s homework.” The extensive amount of time that is devoted to homework also competes with activities that students and families value, including sports, music, recreation, and social experiences.

The research on homework and academic achievement (as measured by standardized test scores) is weak at best: “ …the relationship between homework and academic achievement in the elementary-school years is not yet established …” comes from an article called the “The Case for (Quality) Homework.” While there are more studies that show a correlation between homework and test score improvement at the middle and high school level, these same studies nonetheless are riddled with caveats about variation in the home environments and cautionary notes about the need to limit the amount of homework.

Possibilities of a learner-centered approach to homework

It would not be hard, based on these experiences and information, to make the case that homework is not learner-centered. With that said, we should also push ourselves to consider what it would take to reframe homework for the benefit of all learners. While it is evident that homework is not uniformly beneficial, limiting our view of learning to the confines of a traditional six-hour school day is also not a helpful perspective and one that would constrain our view of what is possible.

Using our learner-centered framework, we would suggest that the right starting point for a more productive conversation about homework is to begin with whole-learner outcomes. What is it that we really seek to accomplish? Wellbeing? Social connection? Creativity? Self-management? Let’s begin by aligning on our aspirations and then we should co-design learning experiences to achieve those outcomes.

Importantly, the learners themselves should be active participants in determining their goals and setting plans to achieve them. While we know that this requires modeling and active support in the co-construction phase, in its ideal state any form of homework would be learner-driven based on their unique strengths, interests, values, context, and goals.

In the words of Colleen Broderick, “learner-centered education is a mindset that stems from the belief that every learner is unique and capable and where all decisions must measure up to the question, ‘What is best for learners?’”

Let’s embrace the uniqueness and capabilities of each and every learner, asking ourselves what is best for each of them as individuals, and let’s reimagine homework as one of the many levers to shift away from a standardized, compliance-focused system to one that embraces personalization, agency, authenticity, and truly honors the process of learning.

What enabling conditions might your school or district adjust to shift to a more learner-centered approach to homework and more? Schedule time with our team for a consultation specific to your learning environment.