5 Powerful Practices to Develop Learner-Centered School Leaders

On a sunny January “winter” day in Santa Ana, California, a group of Assistant Principals huddle around a case study that chronicles a common scenario in their (and many) school districts: a new teacher is struggling with reading instruction and classroom management, and her students report feeling bored and disengaged. The school leaders collaborate with their small groups to develop a year-long coaching strategy for the teacher depicted in the case study, anchoring their analysis in different data “elevations,” from student interview data, to classroom assessments, to standardized testing scores (Safir and Dugan, 2021). Together, the group develops a poster to represent the leadership values and the coaching strategies they will employ, drawing on their learning from the year-long Learner-Centered Leadership Academy.

Why Learner-Centered Leadership Academies?

A Learner-Centered Leadership Academy is a year-long professional learning series designed for school leaders, including principals, assistant principals, instructional coaches and teacher leaders. Leaders work to develop the knowledge, skills and mindsets needed to effectively lead and scale learner-centered change in their schools.

At Learner-Centered Collaborative, we often grapple with how to ensure that a district’s vision for teaching and learning (such as their Portrait of a Learner and Learning Model) doesn’t collect proverbial “dust” on a website in cyberspace. There are many important strategies that a District should consider to actualize their vision, and engaging deeply with leaders should be prioritized among them. As we explore a district’s vision with leaders, we ask them questions like:

- Do you believe it?

- Can you lead it?

- How do you want teachers to feel about this work?

Top Five Practices for Transformational Learning for School Leaders

For anyone considering how to design transformational learning experiences that align leadership development with a district’s vision, we’ve identified five key practices that emerged from the SAUSD Learner-Centered Leadership Academy for Assistant Principals over the 23-24 school year. These practices supported school leaders to bridge theory and practice, bringing the SAUSD vision to life.

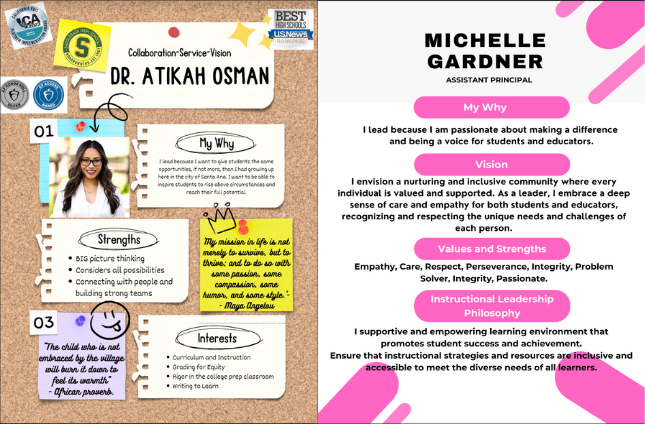

1. Start with Self

If we hope to transform our systems, we have to be courageous enough to start with ourselves. In Santa Ana, we explored our complex and intersectional identities. We articulated our strengths and our values, as humans and as leaders. And most importantly, we got clear about our own narratives – what brings us to this work, and what fuels us to sustain it? This clarity is not only important on a personal level when developing a strong leadership practice, but it’s also an important communication tool for leaders to practice with their communities. The ability to compellingly and clearly share your why, your motivations, and your deepest hopes as a leader invites others into a space of trust and growth alongside you.

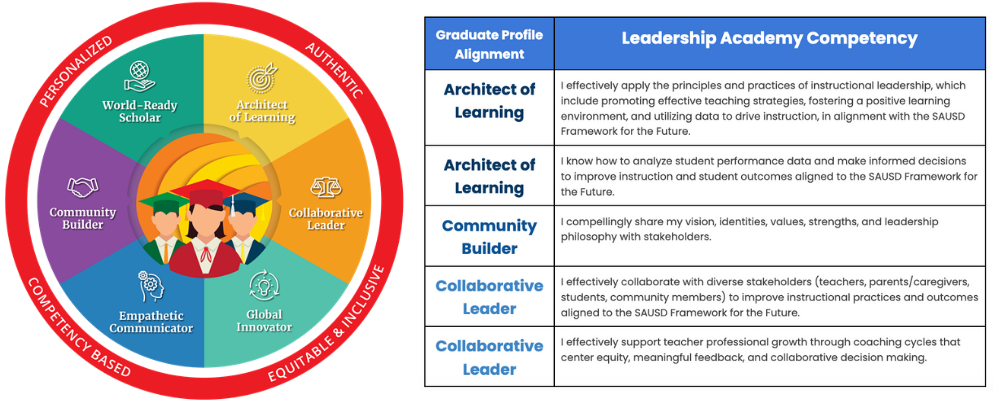

2. Define Clear Competencies

Before diving into the nuances of instructional leadership during our Learner-Centered Leadership Academy, we first worked to get crystal clear about our collective aspirations. We asked, what do we want for learners in this community? Why do these aspirations matter? In Santa Ana, school leaders engaged deeply with the SAUSD vision, the Portrait of a Graduate, and the Learning Model. They connected the district’s vision with their own personal motivations and values. This allowed the group to start pointing our arrows in the same direction, getting clear about what the “instruction” in “instructional leadership” actually means.

We then created a framework for leadership development aligned to the SAUSD Graduate Profile. We explored what it means to be an “architect of learning” and a “community builder” in the context of instructional leadership. Then, we developed a set of leadership competencies to anchor our collective work and to define the knowledge, skills and dispositions we aspired to cultivate during our time together. Participants in the Learner-Centered Leadership Academy regularly assessed and reflected on these competencies, deepening their understanding of effective instructional leadership.

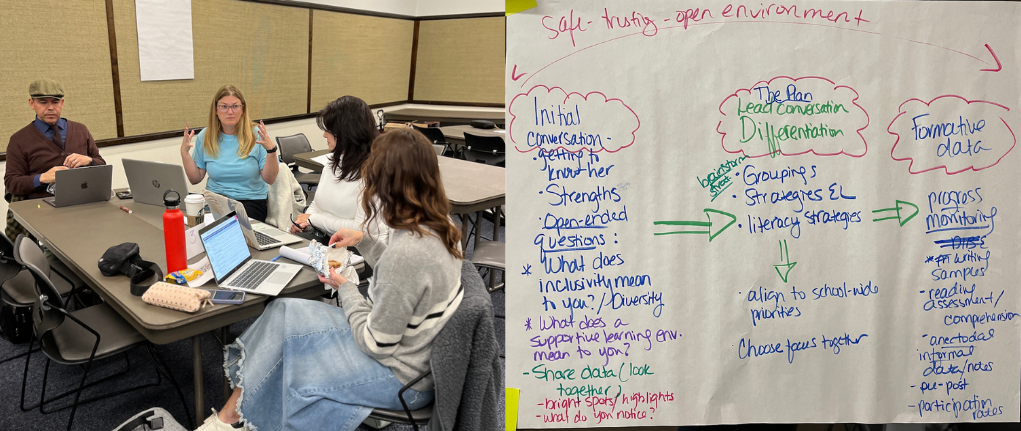

3. Use Case Studies

Case studies are a practical and dynamic tool for engaging school leaders in rich discussion and collaborative problem-solving. By engaging with authentic scenarios containing real data from SAUSD teachers, school leaders were able to bridge theory and practice, devising actionable strategies and sparking deep learning and thinking. Case studies promote a culture of shared learning and distributed leadership, empowering leaders to powerfully draw on each other’s insights and experiences.

4. Try Dilemma Consultancies

The group of Assistant Principals in Santa Ana shared their desire to make time to engage in conversations about the pressing problems of practice they were navigating in real-time. At a few of the sessions, individuals volunteered to share a dilemma in small groups. Facilitators supported each group to move through the stages of the structured discussion protocol as the group grappled with the dilemma, offered insights and ideas, and considered multiple angles and the potential impacts of different solutions. School leaders provided glowing feedback about these discussions. One wrote, “This collaboration was so invigorating and exciting. I left with a sense of pride and connectedness with my colleagues. That night I couldn’t sleep the night. The buzz of all the conversation was spinning in my head. I felt a combined sense of urgency, empowerment and responsibility for children and their future.”

5. Engage in Role Plays

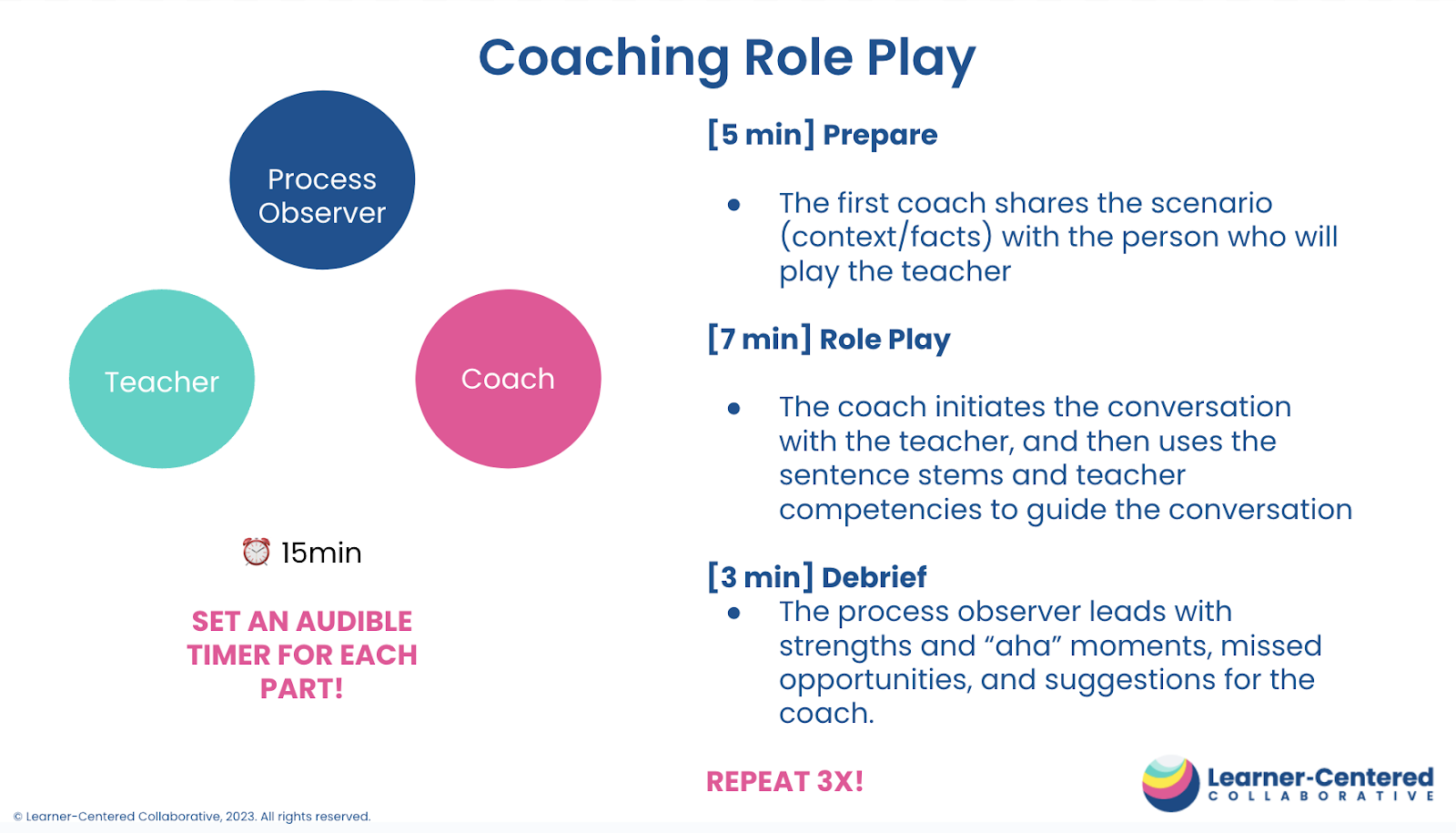

The role play can be an awkward, sweaty palmed endeavor without thoughtful structures in place. In Santa Ana, we anchored in Elena Aguilar’s Coaching Stems, first doing a scavenger hunt for Elena’s artful use of stems in several videos, before trying them out ourselves. Each participant brought a real scenario to the table to ensure that their coaching conversations were authentic and grounded in real context. We coached in triads, using a process observer to guide the debrief conversation after each coaching session. The process observer was keenly focused on how the coach positioned the teacher as the “final decision maker,” honoring their experience, expertise, and instincts instead of “choosing for them” (Knight, 2011).

Nurturing Transformational Leadership

Transformational school leadership is a life-long pursuit and is not mastered in a workshop series. But school leaders deserve opportunities to deeply explore their own complex identities, strengths, and values, and to map them on to those of their colleagues and to the system at large. They deserve to pause and to learn through dialogue, reflection, and social experiences with their peers. Young learners deserve school leaders who are poised to be effective “architects of learning” at their sites, creating the conditions for all learners to know who they are, thrive in community, and actively engage in the world as their best selves.

Ready to engage leaders in building capacity? At Learner-Centered Collaborative, we’re dedicated to supporting educational leaders in creating meaningful change. Whether you’re interested in our customized leadership development programs or want to explore how we can support your school or district, we’d love to hear from you. Connect with us today.

References

Aguilar, E. (2016). The art of coaching teams: Building resilient communities that transform schools. John Wiley & Sons.

Safir, S., & Dugan, J. (2021). Street data: A next-generation model for equity, pedagogy, and school transformation. Corwin.

Knight, J. (2011). What good coaches do. Educational leadership, 69(2), 18-22.