Competency-Based Learning: Shifting from Grading Points to Assessing Learning

I started as a first year teacher, armed with a student teaching experience and a master’s degree, fairly confident that I was well prepared. If you are or have ever been a teacher, you are laughing right now because as you know, I figured out pretty quickly that I had a lot to learn. One of those things was how to grade. On my first day I was given access to our SIS and was given two requirements: 1) I needed a gradebook that had assignments in it by the end of the first week to show families where their students stood in my class, and 2) I was required to have my grading policy on my syllabus.

I quickly realized that I had no idea how to set up a gradebook or what my grading policy would be. My teacher preparation program never had a course on grading. We had talked about backwards design and we created assessments but we never talked about the implications of points v. percentages, how to determine what weighted categories you should have or how many points each assignment should be worth. Like many things with the teaching profession, I learned on the job.

Throughout my first few years of teaching I was frustrated and constantly changing my grading practices and policies. I would think, maybe if I made homework worth only 2 points it would be low stakes enough that it wouldn’t affect their grade but it would encourage them to do it? This stemmed from a belief that students wouldn’t do the homework if I didn’t grade it. The truth was, they probably wouldn’t, because the incentive system they lived in was based on grades. Students would come in towards the end of the semester and ask what they could do to bump their grade up, seeking extra credit opportunities. They would ask things like “is this on the test”, when we were learning something, the question every teacher dreads. I was frustrated with students, when in reality it wasn’t the students, it was me and the system I was perpetuating. I was perpetuating an industrial era, school-centered belief system that is the foundation for our grading structure in the United States with my gradebook and I had no idea.

Aligning Assessment Practices to Modern Learning Sciences

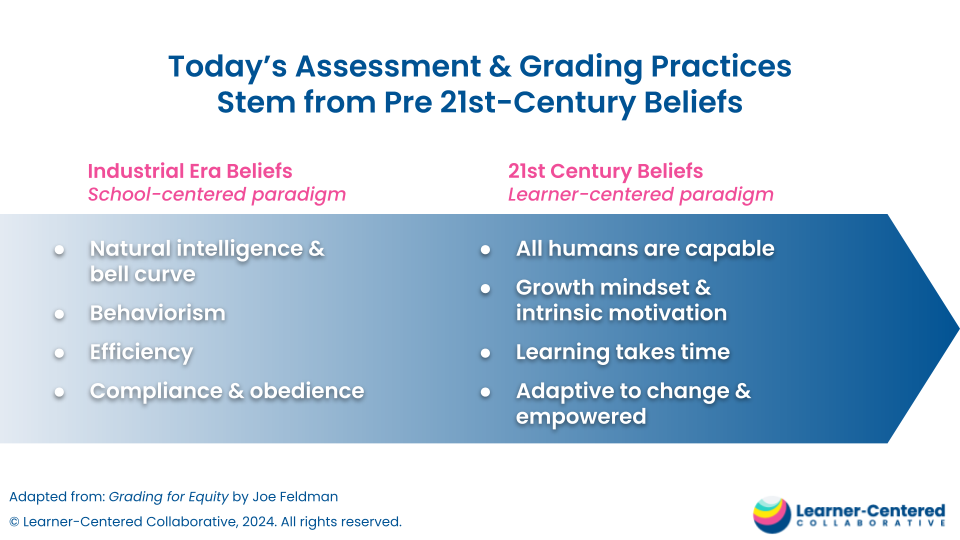

Industrial era beliefs created school-centered systems in the 20th century as schooling became compulsory and expanded to more and more children. At that time, there was a prevalent belief that some humans had the capacity for intelligence and some did not. The idea of the bell curve, that only a small portion of students were naturally capable of succeeding took the idea of natural intelligence further and was founded on racist and elitist notions. In the 21st century we have shifted to a belief system grounded in the idea that all humans are capable, that each of us have unique strengths and can find success in personalized pathways. Our grading system continues to operate however, from a belief system that we must rank students and define intelligence and success in narrow ways.

Behaviorism was another belief system that was strong in the early 20th century, with studies by Skinner in the 1940s finding that humans will learn and behave based on rewards and punishments. This motivation theory has shifted in the 21st century to focus more on developing a growth mindset with research from Carol Dweck and the importance of intrinsic motivation that comes from working towards mastery goals instead of performance goals. However, in classrooms across the country, we use points and grades to encourage students to complete their work or behave a certain way as well as deter some behaviors. A late penalty and a zero for cheating is a legacy of behaviorism at its finest.

The industrial era’s biggest value was efficiency. Decisions about what school looks like, what Tyak and Tobin refer to as the “grammar of schooling”, such as bell schedules, stem from this value. Our grading systems are also designed to be as efficient as possible with mathematical formulas and a focus on churning through the grades rather than focusing on feedback and iteration. Research has shown us though, in the 21st century, that learning takes time. In fact, those cycles of feedback and iteration, learning from mistakes and tinkering with ideas are crucial for the learning process. Focusing on efficiency, or just covering the standards or inputting a score at the end of the semester to fulfill the grading requirements, can come at the detriment of learning.

Finally, the industrial era of school-centered schools were built with a focus on obedience and compliance. In the industrial era it was important for factory workers to follow instructions and the education system was designed to develop those workers. Children of the wealthy had tutors and academic experiences that asked them to apply their learning and solve problems. Compulsory education was for the masses and the masses were intended to comply. And it worked in that it got the results the system was designed to deliver. A longitudinal study by Karen Arnold, found that valedictorians, those who were sorted up to the highest levels because they played the game and checked all of the boxes, grew up to be successful, but they were not change makers who took risks, started new things, or solved problems in creative ways. In the 21st century as the world is rapidly changing with AI and other technologies, we want, and in fact need, our students to have agency, to learn how to learn, to think critically and solve problems. A school model designed for obedience and compliance no longer serve our students as they live in a world that demands more, and yet our grading systems are designed to reward it over learning. A homework completion grade is a perfect example.

So if our grading systems, left over from an industrial era belief system, are not working in our new 21st century paradigm what is the solution? There are many different answers to this question ranging from dropping the zero to ungrading but at Learner-Centered Collaborative we believe a Competency-Based Approach is the best way to honor the values of the 21st century in a learner-centered system.

Clear the way for a competency-based learning approach with these tips for overcoming common objections to mastery-based assessment.

So What is a Competency-Based Approach?

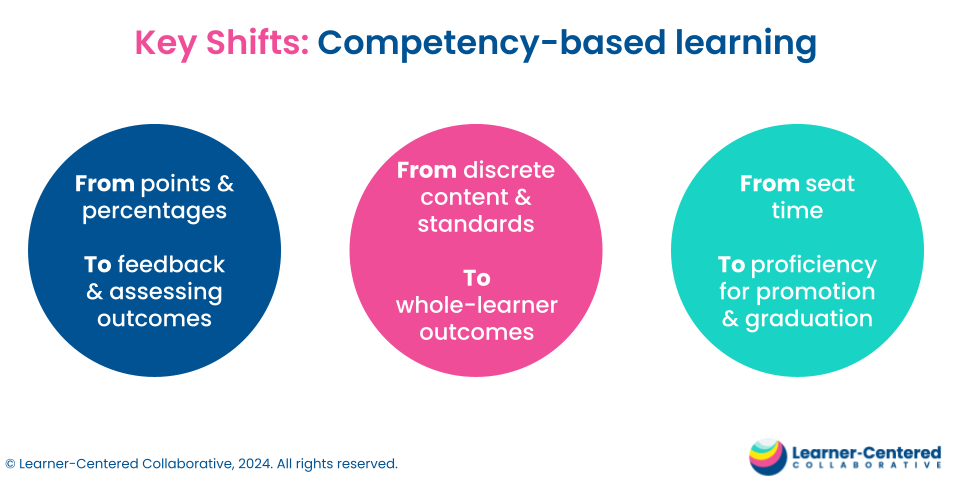

Competency-based learning is an evidence-based approach that emphasizes cycles of feedback and iteration with the ultimate goal that learners demonstrate proficiency on defined learning outcomes. It involves three major paradigm shifts:

1) From points and percentages to feedback and assessing outcomes

A traditional gradebook is organized around assignments that may live in weighted categories. In this paradigm shift, the focus of assessment and therefore the organization of the gradebook and the reporting structures is on the competencies and the assignments or assessments are just the vehicles for providing evidence on the competencies. This shifts the focus away from gaining points through any means necessary such as copying the homework or asking for extra credit to focusing on gaining proficiency in the learning outcomes.

2) From teaching and assessing discrete content and grade-level standards to interdisciplinary, transferable, whole-learner competencies that learners develop over time.

In a learner-centered paradigm, learners are working on a continuum or progression of interdisciplinary, transferable, whole-learner outcomes, called competencies, that demonstrate growth over time. This is a shift from focusing on discrete, content-area and grade-level specific standards to a higher grain-size of competencies that follow a learner throughout their learning journey and incorporate content knowledge and skills alongside real-world skills and dispositions.

3) From measuring seat time to measuring proficiency for promotion and graduation.

This shift is the most challenging to implement as it requires significant policy shifts and collaboration with higher education. In this paradigm, proficiency on key learning outcomes determines when learners are ready to move on. Proficiency also defines promotion and graduation requirements instead of seat time and number of credits in specific courses.

A competency-based learning experience is built on a foundation of whole-learner outcomes, we sometimes refer to as “ladder and knot” outcomes. Audit the outcomes in your practice with this free tool.

These shifts are not things that happen overnight and they represent a full shift to competency-based learning, which today only exists in pockets of education. They take significant mindset shifts that involve examining deeply held beliefs about the purpose of grades, assessment and even learning in a classroom and school. They require changes in classroom practice, structure of courses, new assessment systems and an evaluation of policies and systemic conditions that take time and collective work.

Whether you are a classroom teacher or superintendent, you can take small steps that make a big impact on learners. Which shift might you tackle first?

Many ideas in this blog are inspired by the research and writings of Joe Feldman in Grading for Equity and books and publications of Thomas Guskey.

Transform your assessment practices today.

- Explore our Competency-Based Reporting Playbook

- Dive deeper into competency-based learning with our blog post, “3 Key Shifts from Traditional Grading to Competency-Based Learning and Assessment.”