3 Key Shifts from Traditional Grading to Competency-Based Learning and Assessment

This is the second blog post in a series on Competency-Based Learning from Bryanna Hanson. Read the first post on what competency-based learning is and why it’s important here.

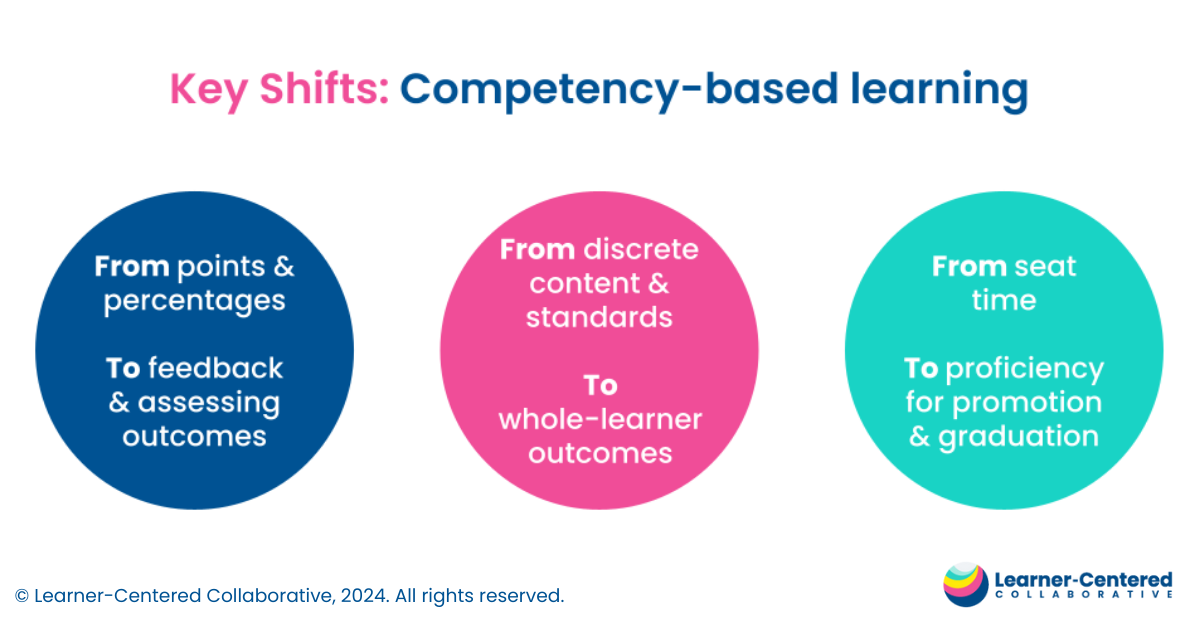

As a teacher, I quickly became frustrated by the limitations of the traditional grading system, one based on points, percentages and averages. This sparked my journey into competency-based learning – an approach that aligns with modern research on how students actually learn and grow. At its core, competency-based learning proposes three transformative shifts: from grading assignments to assessing proficiency on learning outcomes, from fragmented grade-level standards to developing interdisciplinary competencies over time, and from measuring seat time to basing advancement on demonstrated mastery. Making these shifts matters because they empower learners and prepare them to navigate an unpredictable future.

1. From Grading Assignments to Assessing Learning Outcomes

The first shift in competency-based learning is from grading assignments with points and percentages to providing feedback and assessing learning outcomes. In a traditionally graded classroom, the grade book consists of various assignments such as homework, classwork, quizzes, tests, projects, and participation. Students receive points or percentages based on their performance, which may be affected by factors like punctuality or adherence to specific requirements. These points are then averaged, sometimes with weighted categories, to calculate a final grade.

In contrast, in a competency-based learning environment, the grade book is organized by learning outcomes. Assignments, which may still include quizzes, tests, and projects, alongside performance assessments, serve as opportunities for learners to demonstrate their proficiency in specific competencies. This shift in assessment focus also involves a change in how assessments are scored. Instead of relying solely on points or percentages, competency-based approaches may use symbols, letters, numbers (usually 1-4), or descriptive words like emerging, developing, and meeting to indicate proficiency levels.

“By providing learners with a deep understanding and ownership of expectations, their current position to those expectations, and how they can continue to grow, we empower them to take control of their learning journey.”

This paradigm shift encourages learners to focus on gaining proficiency in learning outcomes rather than simply accumulating points by any means necessary, such as copying homework or requesting extra credit. As a Spanish teacher transitioning from traditional grading practices to a competency-based assessment system, I went from assessing quizzes and tests where students earned points (or lost them) to assessing my student’s speaking, reading, writing and listening skills on a proficiency progression scale. My students went from asking “what can I do for extra credit tonight to raise my grade?” to “how do I add more transition words to my writing so I can get to novice high?”

This shift in mindset was a game-changer, but it required dedicating time to educating students about the learning outcomes and proficiency levels. Although some may argue that there isn’t enough time to teach students these concepts or that students cannot grasp the learning goals, it is crucial to develop these skills if we aim to cultivate learners who understand how to learn, have agency over their learning, and become lifelong learners. By providing learners with a deep understanding and ownership of expectations, their current position to those expectations, and how they can continue to grow, we empower them to take control of their learning journey.

2. Shifting to Interdisciplinary Competencies

The second shift in competency-based is from teaching and assessing discrete content and grade-level specific standards to teaching and assessing interdisciplinary, transferable, whole-learner competencies that learners develop on a progression or a continuum over time. This is what distinguishes competency-based learning from standards-based learning.

It is important to note that this shift does not imply that specific knowledge and content skills are not important. Competencies, which live at a larger grain size than standards, embed content area knowledge and skills within them. Foundational reading skills and mathematical literacy remain crucial and are embedded in the competencies. Competency-based learning asserts that these skills need to be applied in various contexts, not just for state tests or specific classes, and developed with other skills such as collaboration and critical thinking. Another distinction is that competencies are skills learners work on over time, plotted on a progression or continuum, as opposed to discrete standards that are accomplished and moved on from in the next grade.

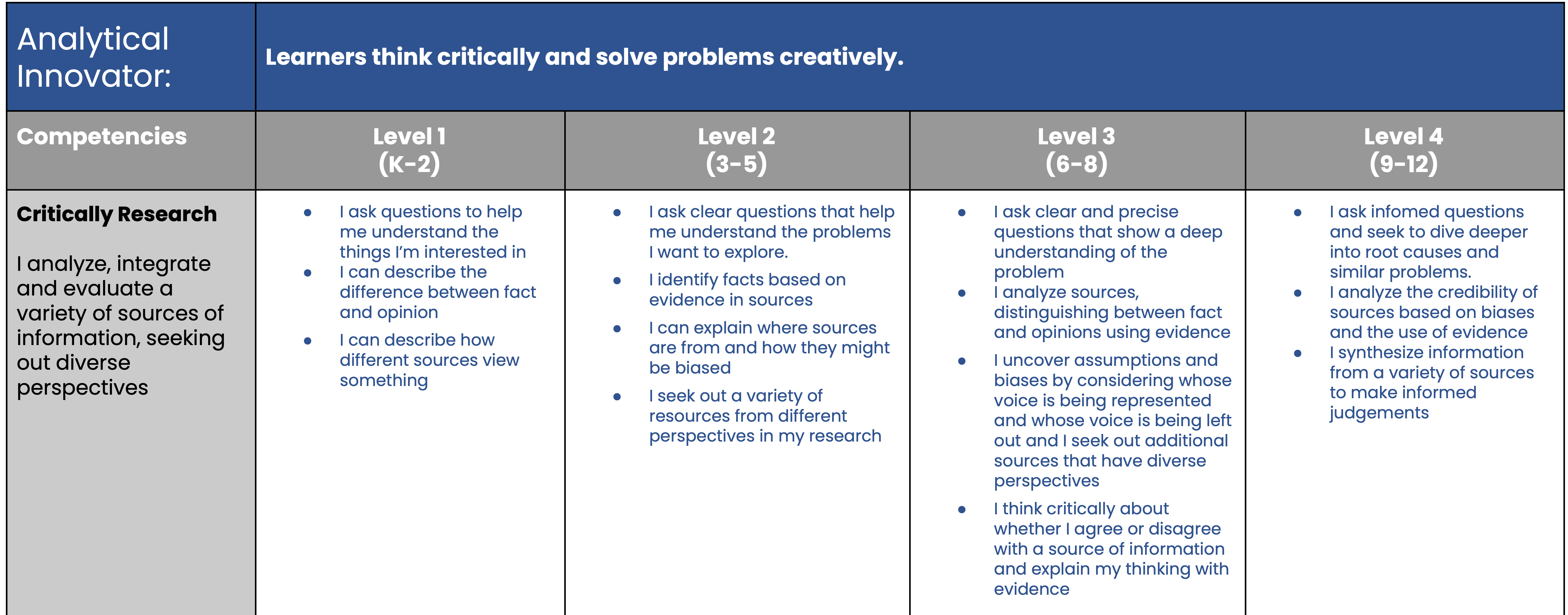

Organizations like Building 21, Redesign and XQ have developed what they call continua that incorporate academic or discipline-specific outcomes and whole-learner outcomes into multi-level progressions that develop over time. At Learner-Centered Collaborative, we support partners in developing similar progressions across grade bands for whole-learner competencies aligned to their Portrait of a Learner, which systems can assess alongside academic outcomes and content area standards. In this paradigm, learners can move up levels across the continua without being tied to specific grade-levels, acknowledging that learners develop at their own pace.

Explore real-life examples of learner portraits and competency progressions in action to see how they can transform your approach to education and unlock each student’s full potential here.

3. Measuring Proficiency Instead of Seat Time

The third major shift in competency-based learning, and the most challenging within the current education paradigm, is the shift from measuring seat time to measuring proficiency for promotion and graduation. The current system assumes that all students in a grade level are ready to move on at the same time, regardless of their individual progress. Yet, why is a first grader ready for second grade at the end of the year just because they have been in 1st grade for 180 days? And how is it possible that all first graders are ready for second grade at the same time? While holding students back can have negative repercussions, passing them along based on seat time – whether they are ready for the next level of learning or not – ensures that they fall further behind academically and in other skills.

What if our promotion and graduation requirements were based on proficiency in important knowledge, skills and dispositions? Some schools, like Red Bridge organize learners in Autonomy Levels with clear success criteria for promotion, breaking down age and grade level barriers. At the high school level, Mastery Transcript Consortium and One Stone are working to provide non-traditional transcripts that acknowledge progress on competencies and redefine what crediting means.

While this shift requires systemic changes, it can also happen on a smaller scale. Educators in a competency-based system with grade-level cohorts and year-long courses can create conditions within that course where learners move on when ready. The Modern Classrooms model exemplifies this approach: educators set requirements for demonstrating proficiency, learners work at their own pace in small groups, independently and through 1:1 conferences, completing mastery checks to move on to the next learning outcome when ready. This approach honors the spirit of competency-based learning within the constraints of a seat-time-based system.

Discover more about the transformative shifts in education from over 10 schools in our upcoming Competency-Based Playbook, set to release in June 2024 – explore the details and sign up for early access here.

What shift are you ready to start with and what is one step to get started?

These three shifts require examining deeply held beliefs about the purpose of grades, assessment, and learning. These three shifts require significant mindset shifts that involve examining deeply held beliefs about the purpose of grades, assessment, and learning. They require changes in classroom practice, course structure, assessment systems, technology tools and policies. At Learner-Centered Collaborative, we are proud to work with partners on these structural shifts. If you’re interested in doing this work within your system, we hope to hear from you.

Let’s Collaborate