Now Is the Time for Learner-Centered, Whole-Child Education

By Devin Vodicka, Kim Smith, Jen Holleran, and Jean-Claude Brizard

This is the full version of a commentary published on EdSource on November 1, 2021.

Throughout the course of the pandemic, we have seen students, families, and educators leaning into the unknown.

Adapting to the rapidly changing modes of in-person, hybrid, and distance learning, teachers have developed new skills and shifted their focus from their own teaching to students’ learning. Parents and families have juggled adjustments in their professional and personal lives, while finding resourceful ways to connect their children to one another. And in the face of isolation, grief, and physical danger, young people have tapped into their interests and strengths and taken increasing ownership of their learning.

It is the ingenuity of so many people – students, families, and educators – that gives us hope and optimism for the future.

In addition, we have seen the value of anytime/anywhere learning that goes beyond the four walls of a classroom. These experiences have helped students to develop a sense of self, to exercise their curiosity and creativity in new ways, and to increase their intrinsic motivation for learning, even when not getting any “credit” for their efforts.

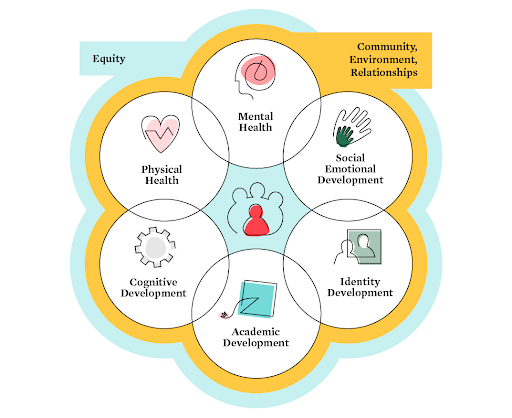

The adaptations that were made, and what we have learned from them, may be the silver linings of this most difficult period in most of our lives. Throughout, all constituencies recognized the importance of the “whole child” and the undeniable interconnectedness of our physical, social, and emotional well being with our cognitive and academic development. The same is equally true for our families and educators: It is by meeting the needs of the whole person that other accomplishments become possible.

Similarly, we now know students learn in many ways, in many places, and from many different experiences. Yet our current assessment systems have no way of capturing data in this area most people now agree is so important. As individuals and as a society, we need to hold onto these hard-earned learnings and build enabling systems around them if our children are to thrive. Emerging models of equity-focused whole-child education such as the one displayed in this graphic are helpful frameworks that can guide our efforts to better support all learners.

Unfortunately, our desire for a return to “normal” and our conditioning to the status quo may be pulling us back to what was familiar before the pandemic, including a singular focus on classroom-based academic development in only reading and mathematics without the full appreciation and understanding that some non-academic competencies are critical to academic development (e.g., executive function and agency). While traditional academic subjects are of course important, there are hazards to focusing myopically on a narrow set of academic outcomes. For example, a study from the University of Maryland found an inverse relationship between raising test scores and student happiness. Even more alarming is the global data showing that high performance on standardized tests is often associated with poor attitudes about the academic subject area itself. These studies remind us that we need to expand our view of student success.

Some may be concerned that offering a wide range of learning activities will dilute academic rigor. It’s important to note that cognitive and neuroscience point to and support a whole child approach to better support academic development. It’s also clear that interest-driven learning and achievement often go hand in hand. Families seek out schools that embrace a wide range of active learning options (sports, arts, other extracurricular activities) and that enable students to find their passions in many places. Independent private schools, which have more latitude to focus on a broader set of student development goals instead of narrow proficiency mandates, are often judged by reputation and longer-term life or postsecondary outcomes as metrics. As a result, they invest significant resources in providing students a plethora of ways to learn and grow.

Measuring whether a school is supporting interest-driven, whole-child development, or not, will be imperative as we evaluate the progress of individual learners and of our collective system.

Schools like Odyssey STEM Academy (California) have shown that when they focus on learner-centered practice and whole-child outcomes, they see improvements in metrics such as college readiness and PSAT results. A charter school from Hawaii, SEEQS implements a rigorous portfolio defense to promote student ownership and demonstrations of progress tied to sustainability skills. Logan County Schools (Kentucky) have developed and implemented measures of habits and skills tied to their graduate profile.

If it wasn’t evident before the pandemic, parents and students are now pretty clear: too narrow of an academic focus on math and English alone just isn’t enough. We must avoid falling back into the one-size-fits-all approach that we know has not worked for all students. We need to expand our view of success to include knowledge, habits, and social and emotional life skills and add more ways to understand what each child knows and can do. (This need is particularly acute now, as students are coming back to school from the pandemic gap at different places in their learning.) Instead of measuring our progress exclusively through standardized tests, we need to clearly articulate a broader set of outcomes including whole-child outcomes and use learner profiles and assessment strategies that add these aspirations to our definition of success.

Now is the time to make the shift to a learner-centered, whole-child model of education for all learners. Throughout the pandemic, students, families, and teachers have shown us the importance of adapting to meet the specific needs of the whole child based on their unique context and interests. Now our educational systems and structures must evolve to do the same.

About the authors

Devin Vodicka is the CEO of Learner-Centered Collaborative and the author of Learner-Centered Leadership. He was recognized as California Superintendent of the Year in 2015 (ACSA) and 2016 (AASA).

Kim Smith is the Founder and former CEO of NewSchools Venture Fund, Bellwether Education Partners, and the Pahara Institute. She focuses on enabling entrepreneurs and innovation to achieve excellence with equity in our public schools.

Jen Holleran is a philanthropic advisor who brings an equity, learner-centered, whole-child vision to the future of learning and school design. She led Startup:Education, (the education precursor to CZI), and was a teacher, principal and nonprofit leader.

Jean-Claude Brizard is the President and CEO of Digital Promise and a former schools superintendent in Chicago, Rochester and NYC Public Schools.