From Data to Storytelling: How Scorecards are Transforming School Accountability in Hawai’i

Written by Nicolas Mireles, Ph.D. Candidate at James Madison University.

Through the inaugural Learner-Centered Assessment Fellowship, Digital Promise and Learner-Centered Collaborative brought together early-career scholars, education partners, and mentors to explore the potential of collaboration and culturally responsive approaches to educational assessment.

As a final reflection and celebration of their work, each of the four research fellows has authored a blog post for Learner-Centered Collaborative. First up is Nicolas Mireles (Ph.D. candidate at James Madison University) who shares his analysis and reflections on the impact learner-centered scorecards are having within the Hawai’i Public Charter School network. Nicolas was mentored throughout the project by Dr. Kent Seidel, associate professor at the University of Colorado Denver.

Historically, legislation like No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) has focused heavily on standardized metrics as the primary tool for school and district accountability. This approach risks narrowing content, overlooking local considerations, and ignoring the diverse learning experiences that make each school unique. Oftentimes, the test scores provide little value for improving instruction, tell an incomplete story about schools, and limit a holistic view of student development.

To address these weaknesses, the Hawaiʻi Public Charter School Commission partnered with Learner-Centered Collaborative to develop an accountability system that actively involves local Hawaiian Public Charter School communities. The Accountability Plus model seeks to collect evidence and data that represent a more holistic picture of student development, including the use of culturally-responsive assessment principles:

- Shared Power

- Engagement

- High Expectations

- Flexibility

- Asset-Based (Walker et al., 2024)

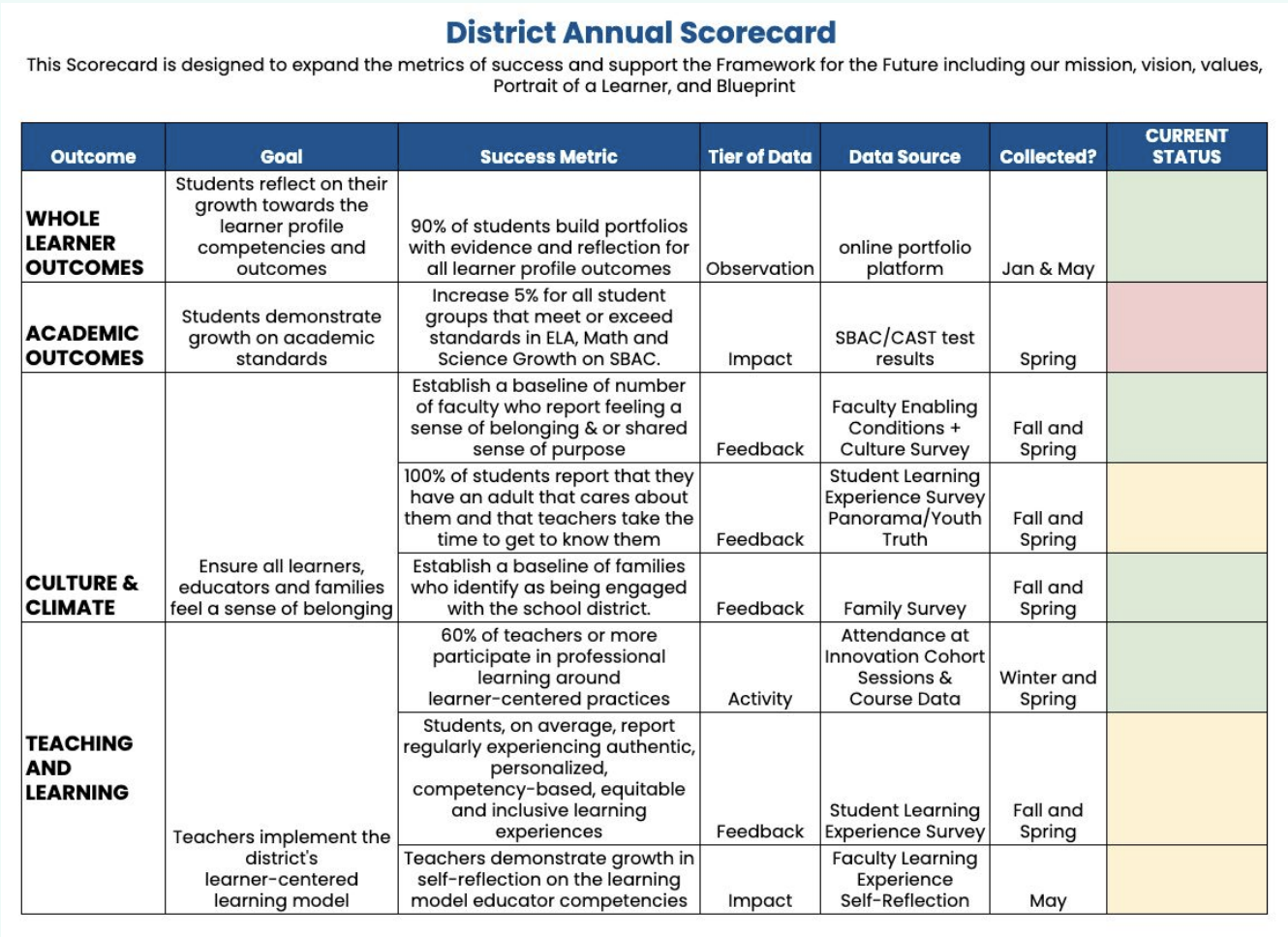

This model aligns assessment with each school’s cultural perspectives. In doing so, it respects the students, teachers (kumu), and communities that shape each school’s identity. The tangible outcome of the Accountability Plus model is unique assessment scorecards for each school. These scorecards articulate desired outcomes, success metrics, and data sources in an easily digestible format.

I had the opportunity, as a researcher, to evaluate these scorecards and look for patterns throughout the Hawaiian charter school network to see how they were being developed and applied in real-world contexts. To conduct my analysis, I applied the first step of the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CBAM)—Innovation Configuration Maps. First developed by Gene Hall and Susan Louck in 1981, Innovation Configuration Maps “represent the patterns of innovation use that result when different teachers put innovations into operation in their classrooms” (Hord et al., 2014).

I used this technique to map out the key components (and their variations) of the assessment scorecards that had been created by each charter school. Components explored included desired outcomes, the scorecard creation process overall, and the impact scorecards are having on classroom practice.

Schools’ Desired Outcome Language Shows Asset-Based Focus

Desired outcomes are the foundation of the scorecard, a critical first step in shaping assessment and empowering school leaders. Each Hawai’ian charter school has its own mission, cultural context, and priorities. I reviewed all desired outcomes within each school’s scorecard and saw that:

- 41% of outcomes were tied to the school’s mission and values

- 39% emphasized student skills

- 20% focused on teachers (kumu), culture, and/or climate

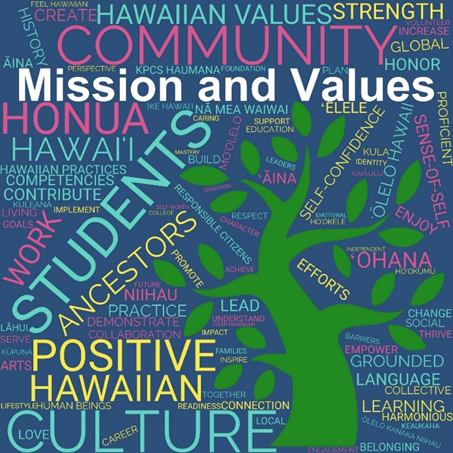

Language choices in these outcomes can either marginalize or celebrate. Hawaiian schools use words that emphasize culture, families (‘ohana), and community values. Furthermore, verbs such as honor, empower, and enjoy, alongside Hawaiian terms, demonstrate an asset-based perspective to student development. To visualize the diversity of themes, I created a word cloud displaying both Hawaiian and English words that highlight each school’s approach to student development.

Scorecards Create a Sense of Ownership and Encourage Collaboration

I spoke with a group of school leaders about the scorecard process, and they shared it not only provided a tool for assessment but also fostered a sense of ownership and collaboration.

Schools appreciated having a structure that aligned with their mission and vision. As one educator said, “We’ve been talking for years about ways to focus more on our mission- and vision-aligned outcomes. The scorecard gave us a framework to prioritize and measure what we value most.”

The empowerment was mirrored with responsibility and high expectations: “If this is what we value, we need a thorough system to measure it mindfully and accurately.”

An unexpected benefit of the scorecard process was a sense of connectedness and community built during the journey for school leaders. Leaders valued sharing successes, challenges, and new ideas while offering support to one another. One participant noted that “the time to collaborate” was crucial because they could use other leaders as sounding boards who offered insights and feedback.

Scorecards Provide a More Complete Picture of Student Development

Some schools have completed their scorecards and are using them to change classroom practices, while others are still drafting theirs with teacher input. Leaders stressed that carving out time and space for teacher training focused on competency-based assessment and reporting practices is vital to avoid burnout. Many also requested expert guidance on how to assess specific outcomes—something they view as an opportunity for further partnership and research support, rather than a desire for top-down directives. Hawaii Technology Academy is one example where this type of guidance is being provided, specifically through Learner-Centered Collaborative’s Competency-Based Community of Practice.

The Accountability Plus model aims to invoke evidence-based storytelling. As Jankowski (2021) notes, assessment stories are not just about data; they are about people, processes, and practices—and the impact those processes and practices have on students and communities.

“It’s been very empowering for our school…because it’s allowed us to go beyond standardized test scores…and find meaningful ways to document what we, as a school, feel is important.” —Hawaiian Charter School Educator

Uniquely, these scorecards offer leaders the evidence they need to tell unspoken stories. Some stories highlight triumphs and cultural celebrations, while others may reveal opportunities for iteration and improvement. All of them reflect a more complete picture of student development that honors the desired outcomes of the local community.

What Comes Next in Hawai’i?

To preserve the authenticity of each school’s mission and maintain high-quality accountability, the next phase for schools after completing their scorecards is collecting data in an intentional way. Assessment professionals play a critical role here, bringing their expertise in designing robust yet flexible processes that yield data suitable for making sound inferences aligned with each assessment’s intended purpose. Furthermore, they can provide insight on considerations of accommodating multiple ways of demonstrating knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Assessment professionals can combine creative and rigorous methodologies with culturally responsive approaches that capture holistic student growth. This adventure—anchored in local ownership and cultural relevance—is still unfolding. With continuous connection and support of school leaders, Learner-Centered Collaborative, and the charter commission, there is every reason to believe this process can remain sustainable, flexible, and maintain its intended purpose.

References

Hord, S. M., Rutherford, W. L., Huling-Austin, L., & Hall, G. E. (2014). Taking charge of change. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Jankowski, N. (2021, January). Evidence-based storytelling in assessment. (Occasional Paper No. 50). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Walker, M. E., Olivera-Aguilar, M., Lehman, B., Laitusis, C., Guzman-Orth, D., & Gholson, M. (2023). Culturally responsive assessment: Provisional principles. ETS Research Report Series, 2023(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12374

Interested in how you can bring learner-centered scorecards to your school or district? Reach out to the Learner-Centered Collaborative team to start a conversation. Contact us here.