Reading, Writing, and Rising: Centering Literacy in Learner-Centered Education

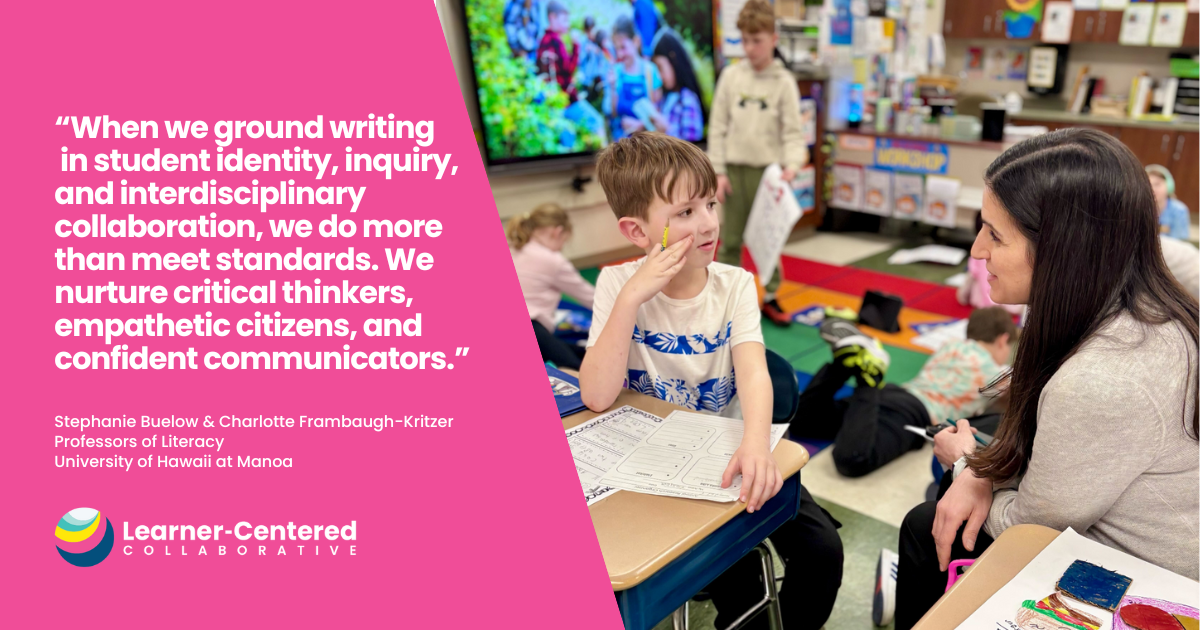

By Stephanie Buelow and Charlotte Frambaugh Kritzer, Professors of Literacy at the University of Hawaii at Manoa

Literacy is the cornerstone of a learner-centered education—it unlocks the ability to think critically, communicate effectively, and engage meaningfully in a rapidly changing world. Few leaders embody this understanding as powerfully as Dr. Lori Gonzalez. A visionary superintendent, Dr. Gonzalez not only champions the development of future-ready skills like problem solving, collaboration, and agency, but deeply recognizes that these competencies are built on a strong foundation of reading and writing proficiency. Her commitment to literacy goes beyond rhetoric; she has led with both heart and strategy.

In Lamont Elementary School District, Dr. Gonzalez prioritized the pedagogical practices that empower learners while also attending to the essential change management needed to make those practices sustainable and accessible to all teachers to ensure students had high quality, research-based literacy instruction. From allocating time and resources to investing in the professional growth of every teacher, her leadership exemplifies what it takes to create learner-centered environments across all grade levels.

In today’s classrooms, learner-centered pedagogical approaches invite us to see students not as passive recipients of knowledge, but as active makers of meaning, identity, and change. It’s a shift that engages the whole learner: their creativity, emotions, languages, experiences, and voice.

To support this vision, we had the privilege of working with Pre-K-8 teachers in Lamont Elementary School District (LESD) with a focus on learner-centered literacy practices, in partnership with Learner-Centered Collaborative.

Our goal wasn’t just to improve reading and writing outcomes; it was to reimagine how literacy could foster student ownership, engagement, and purpose while building the essential skills outlined in LESD’s Learner Profile. This shift lies at the heart of Lamont’s PACE framework: Personalized, Authentic, Competency-Based, and Equitable and Inclusive Learning. Below, we share how these principles came to life in our time with LESD educators.

Lamont’s PACE Framework is inspired by Learner-Centered Collaborative’s Learning Model. Explore how Learner-Centered Collaborative supports partner schools and districts to develop a Portrait of a Learner and Learning Model here.

Lamont Elementary School District’s Learner Profile and PACE Learning Model, developed in collaboration with Learner-Centered Collaborative

Personalized Learning: Honoring Students’ Identity with Choice in the Writer’s Workshop

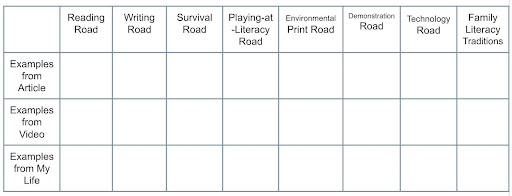

We began the year by having teachers read excerpts from Yetta Goodman’s Multiple Roads to Literacy. This book challenges narrow definitions of literacy and highlights the many unique, valid paths individuals can take to become literate. It encourages teachers to broaden their understanding of what counts as literacy, particularly in culturally and linguistically diverse communities.

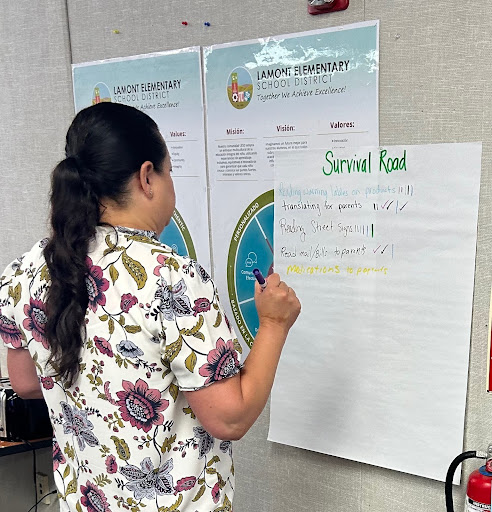

After identifying key examples from the book, we invited teachers to reflect on their own roads to literacy. Teachers recounted not only their traditional reading and writing experiences, but also ways their literacy was developed through play, in their environment, through family traditions, as an act of survival, how it was demonstrated, and through technology.

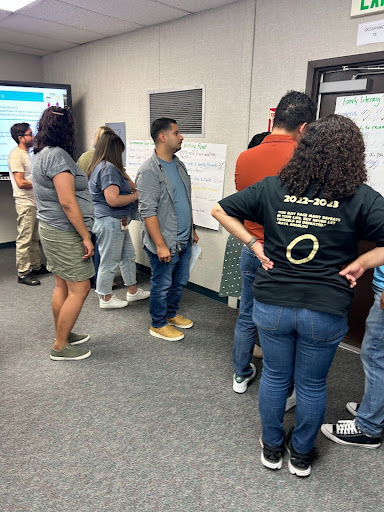

Next, they participated in a gallery walk of their colleagues’ responses. These reflections laid a critical foundation for the work ahead, emphasizing that every learner enters the classroom with a rich, diverse set of experiences, knowledge, and cultural practices and that effective literacy instruction must be responsive to the whole child.

Educators reflecting on their multiple roads to literacy

After establishing a shared understanding of literacy, we turned to effective writing instruction by introducing the Writers’ Workshop Model and emphasizing the writing process, student choice, voice, and agency.

Opinion and argumentative writing nurture the whole learner, supporting academic growth while also developing identity, confidence, and a sense of purpose. In a Writers’ Workshop, students write about issues that matter to them, such as advocating for more recess time or addressing environmental concerns. They begin to see writing as a tool for impact, not just a school assignment. Choice drives engagement, cultivating agency and affirming the belief that every student has something worth saying.

LESD educators participating in the gallery walk of their colleagues’ Roads to Literacy responses

Yet, traditionally, opinion and argument writing is taught with a teacher-generated topic and a narrow formula where students state a claim, support it with three points, and conclude. While organizational structure has its place, this approach often limits students’ creativity, personal voice, and connection to real-world relevance.

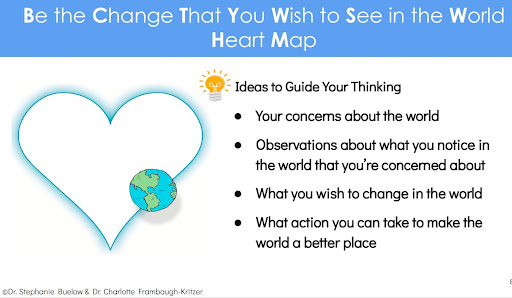

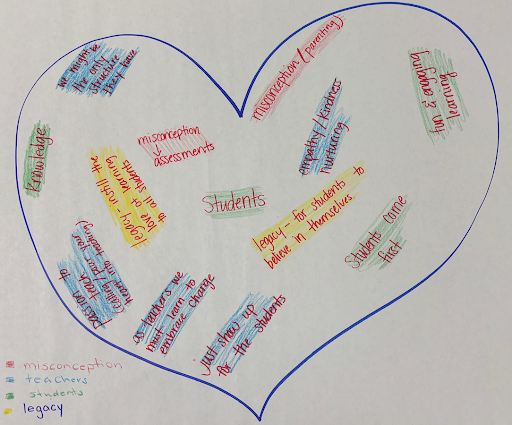

To support a mindset shift, we engaged teachers through the writing process for an opinion (K-5) and argument writing (6-12) piece. We started this work with a strategy called Heart Maps. This gave them firsthand experience before guiding their students in visually representing the people, places, ideas, and passions closest to their hearts. In completing this activity, the teachers could see how these maps can become powerful springboards for opinion writing rooted in personal identity.

Prompts used to guide educators’ Heart Maps

We also explored how the Heart Maps might be personalized across grade levels. For example, in younger grades, Heart Maps might include drawings and simple labels of personal experiences, wonderings, and interests, while in upper grades they often reflect more complex themes, personal questions, and causes students care about. No matter the grade level, the goal is for students to express who they are, highlighting the transformative potential of personalized writing instruction that centers on the writer rather than the writing.

One LESD Educator’s Heart Map

Authentic Learning: Grounded in Real-World Challenges and Audience

We emphasized our shared belief that writing should go beyond a formula. It should be rooted in purpose and designed to make an impact in our work with LESD.

In our work with PreK-K teachers, we focused on how foundational oral language development supports early opinion writing. We shared the guiding belief: you have to think it, to say it, to write it. Rather than pushing young students too quickly into written expression, we emphasized honoring the developmental arc of language.

Teachers learned how to use shared read-alouds, turn-and-talk routines, sentence stems, and guided discussions as experiences for students to verbalize their opinions and build confidence as communicators. This progression, from thinking to speaking to writing, aligns with learner-centered principles and demonstrates how oral language can become a scaffold for writing independence.

With 7th and 8th grade teachers, we explored how authentic writing can emerge from real-world, interdisciplinary inquiry. To support this interdisciplinary work, we introduced the concept of symphonic thinking, which invites educators to step back and consider the full orchestra instead of focusing on a single instrument.

Teachers reflected on key questions:

- Where are we teaching argument writing in isolation?

- What would it take to shift toward a symphony?

- What essential questions could unite us across disciplines?

Each teacher reflected on the strengths of their discipline, offering their own “instrument” to help create a richer, more meaningful learning experience. They discovered how authentic writing connects students to real-world challenges, empowers them to make their voices heard, and positions them as active participants in their communities.

They saw their roles as the following:

- Social Studies: Crafting debatable historical claims

- Science: Evaluating evidence versus opinion

- ELA: Integrating quotes and analyzing sources

- Math: Identifying logical fallacies in data

What stood out was their openness. LESD ELA, science, social studies, and math teachers then engaged in small-group discussions about how they might integrate writing instruction across their disciplines, and how they each could support students in an interdisciplinary shared inquiry.

Competency-Based Learning: Success Criteria and Feedback Cycles

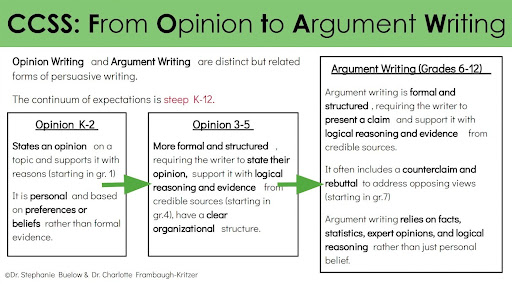

Competency-based learning centers clear goals and ongoing feedback. To ground our work in opinion (K-5) and argument writing (6-12), we spent time analyzing the language of California CCSS Writing Standard 1. Teachers noted nuanced shifts in language from grade to grade, gaining a birds-eye view of the demands the standards require of students across the district.

In a learner-centered Writers’ Workshop, feedback isn’t just about correction: it’s about growth, connection, and reflection. To support the feedback cycle of the writing process, we introduced teachers to a foundational aspect of a Writer’s Workshop that emphasizes growth and reflection over final products: feedback cycles.

In the “2 Stars and a Wish” peer feedback strategy, students name two specific strengths in a peer’s writing and offer one suggestion for growth. This builds a culture of supportive critique and helps students internalize what strong writing looks and sounds like. Feedback becomes relational and actionable.

Equitable and Inclusive Learning: Ensuring Access Through Play and Process

Equity and inclusion demand that we create spaces where every student feels seen, heard, and valued. It also means ensuring equitable access to the curriculum.

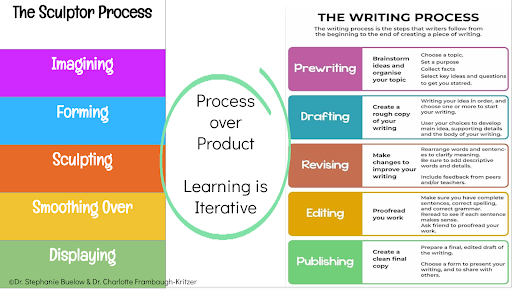

One way we support equitable access is through the use of hands-on manipulatives in the writing process. Offering alternative entry points into writing by making abstract thinking visible and tactile supports students who may struggle with traditional forms of expression due to language development or processing differences.

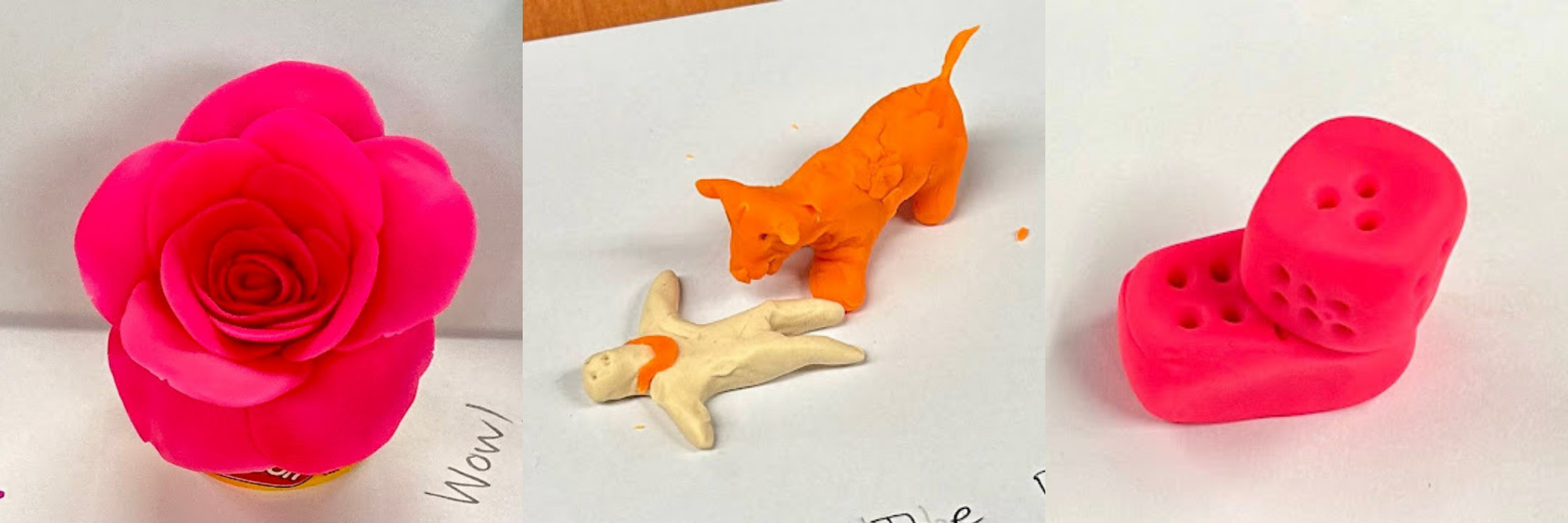

These alternative approaches create low-risk opportunities to engage in the writing process. With this in mind, we introduced teachers to the writing process through an unexpected medium: play-doh. In this exercise, educators considered how to express ideas, play with structure, and reflect on their choices. The result? Sculptures that morphed and evolved while mirroring the messiness of the writing process.

LESD Educators using the “2 Stars and a Wish” feedback strategy to engage with their peers’ play doh sculptures

Why This Matters for Systems-Level Change

These shifts and instructional strategies have had a large impact on Lamont’s learners. The district’s iReady scores show incredible growth. By spring, the percentage of students on or above grade level in reading more than doubled compared to the fall.

However, making learning personalized, authentic, competency-based, and equitable is not just a set of instructional strategies; they are acts of re-centering the learner. When we ground opinion and argument writing in student identity, inquiry, and interdisciplinary collaboration, we do more than meet standards. We nurture critical thinkers, empathetic citizens, and confident communicators.

LESD Educators made creative play doh sculptures

Systemic support is key. School and district leaders can amplify this work by prioritizing the writer over the writing, the developmental arc of language, providing interdisciplinary planning time, revising pacing guides to allow for inquiry, and modeling learner-centered leadership that includes teacher voice.

As Katie Martin reminds us, a learner-centered paradigm supports the development of whole-learner outcomes. It equips students not only to thrive academically, but to know themselves, contribute to community, and thrive as their best selves in the world.

Throughout this blog, we’ve shared learner-centered strategies every educator can take and implement in their classroom. Check out all of Learner-Centered Collaborative’s strategies and self-paced courses to explore more.