Using Feedback to Drive Learning, Connection, Purpose, and Ownership

As a beginning teacher, I remember grading my student essays and marking up the margins with comments, asking questions, probing for more, and then assigning the grade. I spent an inordinate amount of time as an English teacher grading essays like this. Then I would hand them back; my students looked at the grade, and very few paid any attention to the comments I had made. We quickly moved on. What I had done was the equivalent of an autopsy. The final product had already been completed, and I hadn’t built in the time or the expectation to go back to revise or to improve it. I had invested a lot of time and energy giving feedback and writing really thoughtful comments at the most ineffective time in the learning process—after it was over.

Here’s a scenario that I see often:

- Teacher teaches a lesson

- Student receives an assignment

- Student is expected to do the assignment

- Student submits assignment

- Student receives grade for completing the assignment

- Move on

A gentle reminder: This is not teaching. This is evaluating.

Don’t get me wrong, there is a place for evaluation, and it needs to happen sometimes, but it shouldn’t be confused or substituted for the learning process. When we only focus on the end result, we fail to communicate to learners the importance of sharing ideas early, receiving feedback, and revising to improve. If we don’t honor the learning process, we communicate a fixed mindset where they either get it or don’t, and learners often fail to see how the work has value to them personally.

Many will say this takes more time. You are right. You can’t cover it all and go deep. You have to prioritize the goals and identify what matters most and focus on that.

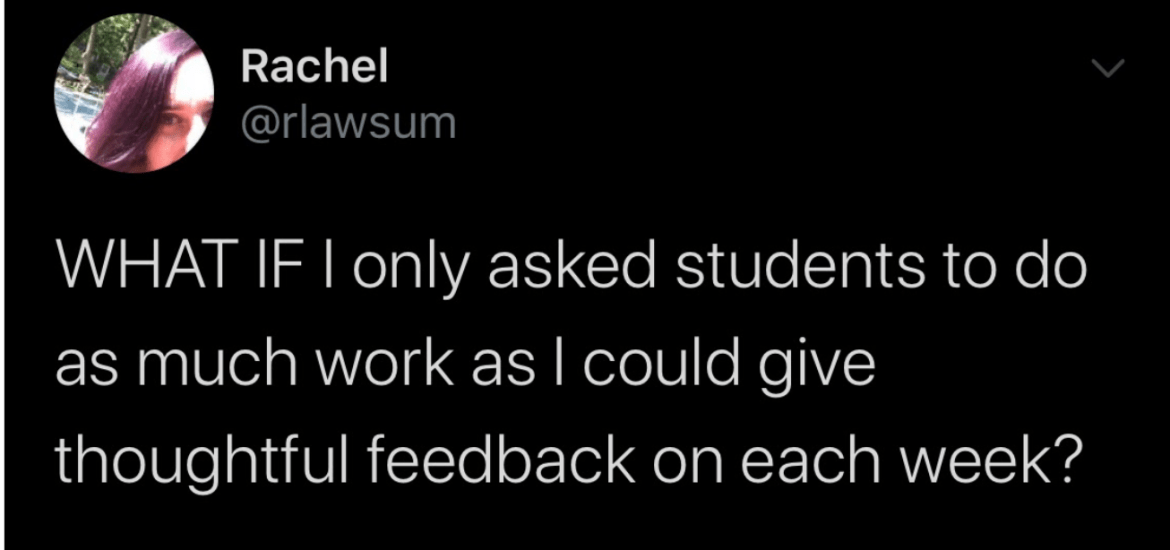

I love this provocation from a teacher that I saw on Twitter:

It sounds so simple and effective, and we know that this would not only save time but also improve the quality of the learning. Innovation in education is not just about adding; it is also about subtracting and evolving how we do things. Instead of taking on the giant workload of providing feedback after the school day, teachers can carve out time during the day and build in structures for feedback to create a sense of connection, purpose and ownership. Furthermore, feedback need not always even be from the teacher. It can come in the form of self-assessment or peer-feedback—with the teacher role being to help students become skilled at these practices, which will be valuable well beyond their school years.

Take stock of what’s working, not working, and ripe for innovation with our free “Continue, Start, Stop Protocol” tool.

Here are 3 ways for students to get and give meaningful and timely feedback:

Self Assessment:

When students are clear on the learning goals and criteria for success, they can assess their own work and take ownership of the process. Checklists and rubrics can be really helpful, especially if they are co-created and students have a clear grasp of what is expected of them. Creating time and building the routine for this practice is critical to understand where students are and determine next steps.

Peer Feedback:

Although self assessment is important, we may not always see the big picture and can benefit from other perspectives. Peer feedback provides opportunities to get new ideas and illuminate blind spots. Some simple structures can help students (and adults) provide kind, specific, and helpful feedback such as Wows and Wonders or critical friends protocols where students identify a question for feedback and their peers ask clarifying questions and provide feedback. This process is helpful for the students getting and giving the feedback. As everyone becomes clearer about the learning targets and discusses the work in relation to it, everyone learns to improve.

Teacher Feedback:

This is usually the most common type of feedback but it takes a lot of time to give feedback to all of your students, and it is not always timely or useful if all the work falls on the teachers. 5-minute conferences can be a really powerful way to check in with students and provide timely meaningful feedback based on their needs. Ideally, check-in focus and feedback should be aligned to a specific outcome that has been previously established by the goals and success criteria of the assignment—making the practice more sustainable for the teacher and more actionable for the learner. For example, if the learning focus is on the organization of an essay, feedback on grammar mistakes is not necessary at that point.

Level-up how you use feedback and assessment AS learning in our online, self-paced course, Use Assessment as a Tool for Learning.

Unlocking time and space for meaningful feedback

If we go back to the initial scenario and make time for learner-centered feedback practices, it might look something like this:

- Teachers and students discuss learning goals, success criteria and models to create a shared understanding of expectations and goals.

- Students engage in a variety of meaningful learning experiences to build knowledge and skills that will help them be successful (such as reading, writing, hands-on experiments, video tutorials, etc).

- Students demonstrate their learning and share with peers, teachers, and other experts who provide feedback along the way.

- Students self-assess and reflect on feedback from others

- Students revise their work, repeating cycles of feedback and revision as needed.

- Student work is evaluated by the teacher, possibly for a grade, referencing the success criteria, student self-reflection and peer feedback.

Meaningful feedback is not the same as a grade or an evaluation. Feedback is information for the learner about where they are in relationship to the goal or target to help them get there. If we can prioritize the learning goals and only assign meaningful work, we can make the time for students to go deep, get feedback, revise, and do something meaningful.

Looking for more? Check out our library of competency-based strategies and self-paced courses to deepen your assessment practices.